After decades of progress, life expectancy long regarded as a singular benchmark of a nation’s success peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years, then drifted downward even before the coronavirus pandemic. Among wealthy nations, the United States in recent decades went from the middle of the pack to being an outlier. And it continues to fall further and further behind.

A year-long Washington Post examination reveals that this erosion in life spans is deeper and broader than widely recognized, afflicting a far-reaching swath of the United States.

While opioids and gun violence have rightly seized the public’s attention, stealing hundreds of thousands of lives, chronic diseases are the greatest threat, killing far more people between 35 and 64 every year, The Post’s analysis of mortality data found.

Heart disease and cancer remained, even at the height of the pandemic, the leading causes of death for people 35 to 64. And many other conditions — private tragedies that unfold in tens of millions of U.S. households — have become more common, including diabetes and liver disease. These chronic ailments are the primary reason American life expectancy has been poor compared with other nations.

Sickness and death are scarring entire communities in much of the country. The geographical footprint of early death is vast: In a quarter of the nation’s counties, mostly in the South and Midwest, working-age people are dying at a higher rate than 40 years ago, The Post found. The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.

Choropleth map of death rates by county

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the country’s economic, political and racial divides. America is increasingly a country of haves and have-nots, measured not just by bank accounts and property values but also by vital signs and grave markers. Dying prematurely, The Post found, has become the most telling measure of the nation’s growing inequality.

The mortality crisis did not flare overnight. It has developed over decades, with early deaths an extreme manifestation of an underlying deterioration of health and a failure of the health system to respond. Covid highlighted this for all the world to see: It killed far more people per capita in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

Line charts showing the percentage increase in income and death rate gaps, along with a death rates of the poorest and richest counties.

Chronic conditions thrive in a sink-or-swim culture, with the U.S. government spending far less than peer countries on preventive medicine and social welfare generally. Breakthroughs in technology, medicine and nutrition that should be boosting average life spans have instead been overwhelmed by poverty, racism, distrust of the medical system, fracturing of social networks and unhealthy diets built around highly processed food, researchers told The Post.

The calamity of chronic disease is a “not-so-silent pandemic,” said Marcella Nunez-Smith, a professor of medicine, public health and management at Yale University. “That is fundamentally a threat to our society.” But chronic diseases, she said, don’t spark the sense of urgency among national leaders and the public that a novel virus did.

America’s medical system is unsurpassed when it comes to treating the most desperately sick people, said William Cooke, a doctor who tends to patients in the town of Austin, Ind. “But growing healthy people to begin with, we’re the worst in the world,” he said. “If we came in last in the next Olympics, imagine what we would do.”

The Post interviewed scores of clinicians, patients and researchers, and analyzed county-level death records from the past five decades. The data analysis concentrated on people 35 to 64 because these ages have the greatest number of excess deaths compared with peer nations.

What emerges is a dismaying picture of a complicated, often bewildering health system that is overmatched by the nation’s burden of disease:

Chronic illnesses, which often sicken people in middle age after the protective vitality of youth has ebbed, erase more than twice as many years of life among people younger than 65 as all the overdoses, homicides, suicides and car accidents combined, The Post found.

The best barometer of rising inequality in America is no longer income. It is life itself. Wealth inequality in America is growing, but The Post found that the death gap — the difference in life expectancy between affluent and impoverished communities — has been widening many times faster. In the early 1980s, people in the poorest communities were 9 percent more likely to die each year, but the gap grew to 49 percent in the past decade and widened to 61 percent when covid struck.

Life spans in the richest communities in America have kept inching upward, but lag far behind comparable areas in Canada, France and Japan, and the gap is widening. The same divergence is seen at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder: People living in the poorest areas of America have far lower life expectancy than people in the poorest areas of the countries reviewed.

Forty years ago, small towns and rural regions were healthier for adults in the prime of life. The reverse is now true. Urban death rates have declined sharply, while rates outside the country’s largest metro areas flattened and then rose. Just before the pandemic, adults 35 to 64 in the most rural areas were 45 percent more likely to die each year than people in the largest urban centers.

“The big-ticket items are cardiovascular diseases and cancers,” said Arline T. Geronimus, a University of Michigan professor who studies population health equity. “But people always instead go to homicide, opioid addiction, HIV.”

The life expectancy in Louisville, where this cemetery lies, is roughly two years shorter than the national average, and the gap has tripled since 1990.

Behind all the mortality statistics are the personal stories of loss, grief, hope. And anger. They are the stories of chronic illness in America and the devastating toll it exacts on millions of people — people like Bonnie Jean Holloway.

For years, Holloway rose at 3 a.m. to go to her waitress job at a small restaurant in Louisville that opened at 4 and catered to early-shift workers. Later, Holloway worked at a Bob Evans restaurant right off Interstate 65 in Clarksville, Ind. She often worked a double shift, deep into the evening. She was one of those waitresses who becomes a fixture, year after year.

Those years were not kind to Holloway’s health.

She never went to the doctor, not counting the six times she delivered a baby, according to her eldest daughter, Desirae Holloway. She was covered by Medicaid, but for many years, didn’t have a primary care doctor.

She developed rheumatoid arthritis, a severe autoimmune disease. “Her hands were twisted,” recalled friend and fellow waitress Dolly Duvall, who has worked at Bob Evans for 41 years. “Some days, she had to call in sick because she couldn’t get herself walking.”

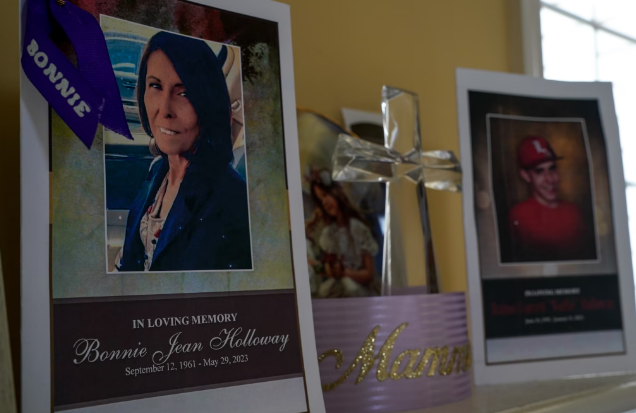

Two funeral programs on a mantel in Louisville attest to the toll of disease in one American family. Dalton Holloway, 30, died in January, after being diagnosed with lung cancer. His mother, Bonnie Jean Holloway, 61, died in May after years beset by chronic illnesses.

The turning point came a little more than a decade ago when Holloway dropped a tray full of water glasses. She went home and wept. She knew she was done.

Her 50s became a trial, beset with multiple ailments, consistent with what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found — that people with chronic diseases often have them in bunches. She was diagnosed with emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — known as COPD — and could not go anywhere without her canister of oxygen.

Her family found the medical system difficult to trust. Medicines didn’t work or had terrible side effects. Drugs prescribed for Holloway’s autoimmune disease seemed to make her vulnerable to infections. She would catch whatever bug her grandkids caught. She developed a fungal infection in her lungs.

Tobacco looms large in this sad story. One of the signal successes of public health in the past half-century has been the drop in smoking rates and associated declines in lung cancer. But roughly 1 in 7 middle-aged Americans still smokes, according to the CDC. Kentucky has a deep cultural and economic connection to tobacco. The state’s smoking rates are the second-highest in the nation, trailing only West Virginia. Holloway began smoking at 12, Desirae said. And for a long time, restaurants still had a smoking section right next to the nonsmoking section.

Desirae Holloway, with her 2-year-old daughter Aliana Starks, attends a volleyball game of her 13-year-old daughter, Ahmya Starks in Louisville in September.

“Her mother was a smoker, her father was a smoker,” Desirae said. “I think I was the one in the family that broke that cycle. I remember what it was like to grow up in the house where the house was filled with smoke.”

In June 2022, Bonnie Jean’s son Dalton, known to his family as “Wolfie” — a smoker, too — went to the emergency room with what he thought was a collapsed lung. After an X-ray, he was prescribed a muscle relaxer. The pain persisted. A second scan led to a diagnosis of lung cancer, Stage 4.

Dalton died in the hospital on Jan. 31. He was 30.

A concert enlivens the banks of the Ohio River on June 2 in Jeffersonville, Ind., in the shadow of Louisville.

In 1900, life expectancy at birth in the United States was 47 years. Infectious diseases routinely claimed babies in the cradle. Diseases were essentially incurable except through the wiles of the human immune system, of which doctors had minimal understanding.

Then came a century that saw life expectancy soar beyond the biblical standard of “threescore years and ten.” New tools against disease included antibiotics, insulin, vaccines and, eventually, CT scans and MRIs. Public health efforts improved sanitation and the water supply. Social Security and Medicare eased poverty and sickness in the elderly.

The rise of life expectancy became the ultimate proof of societal progress in 20th century America. Decade by decade, the number kept climbing, and by 2010, the country appeared to be marching inexorably toward the milestone of 80.

It never got there.

Multiple charts showing rates of different causes of death

Partly, that is a reflection of how the United States approaches health. This is a country where “we think health and medicine are the same thing,” said Elena Marks, former health and environmental policy director for the city of Houston. The nation built a “health industrial complex,” she said, that costs trillions of dollars yet underachieves.

“We have undying faith in big new technology and a drug for everything, access to as many MRIs as our hearts desire,” said Marks, a senior health policy fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “Eighty-plus percent of health outcomes are determined by nonmedical factors. And yet, we’re on this train, and we’re going to keep going.”

The opioid epidemic, a uniquely American catastrophe, is one factor in the widening gap between the United States and peer nations. Others include high rates of gun violence, suicides and car accidents.

But some chronic diseases — obesity, liver disease, hypertension, kidney disease and diabetes — were also on the rise among people 35 to 64, The Post found, and played an underappreciated role in the pre-pandemic erosion of life spans.

From left, Mike Lottier, Derrick Jones and Langston Gaither gather at a cigar bar in Jeffersonville, Ind., in June.

In 2021, according to the CDC, life expectancy cratered, reaching 76.4, the lowest since the mid-1990s.

The pandemic amplified a racial gap in life expectancy that had been narrowing in recent decades. In 2021, life expectancy for Native Americans was 65 years; for Black Americans, 71; for White Americans, 76; for Hispanic Americans, 78; and for Asian Americans 84.

Death rates decreased in 2022 because of the pandemic’s easing, and when life expectancy data for 2022 is finalized this fall, it is expected to show a partial rebound, according to the CDC. But the country is still trying to dig out of a huge mortality hole.

For more than a decade, academic researchers have disgorged stacks of reports on eroding life expectancy. A seminal 2013 report from the National Research Council, “Shorter Lives, Poorer Health,” lamented America’s decline among peer nations. “It’s that feeling of the bus heading for the cliff and nobody seems to care,” said Steven H. Woolf, a Virginia Commonwealth University professor and co-editor of the 2013 report.

In 2015, Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton garnered national headlines with a study on rising death rates among White Americans in midlife, which they linked to the marginalization of people without a college degree and to “deaths of despair.”

The grim statistics are there for all to see — and yet the political establishment has largely skirted the issue.

“We describe it. We lament it. We’ve sort of accepted it,” said Derek M. Griffith, director of Georgetown University’s Center for Men’s Health Equity. “Nobody is outraged about us having shorter life expectancy.”

The Joslin Diabetes Center sits along a stretch of road in New Albany, Ind., dotted with fast-food restaurants.

It can be a confusing statistic. Life expectancy is a wide-angle snapshot of average death rates for people in different places or age groups. It is typically expressed as life expectancy at birth, but the number does not cling to a person from the cradle as if it were a prediction. And if a country has an average life expectancy at birth of 79 years, that doesn’t mean a 78-year-old has only a year to live.

However confusing it may be, the life expectancy metric is a reasonably good measure of a nation’s overall health. And America’s is not very good.

The Jeffersonville waterfront offers a view of the Louisville skyline. The Louisville metropolitan area includes urban, suburban and rural communities that have health challenges typical in the heartland.

For this story, The Post concentrated its reporting on Louisville and counties across the river in southern Indiana.

The Louisville area does not, by any means, have the worst health outcomes in the country. But it possesses health challenges typical in the heartland, and offers an array of urban, suburban and rural communities, with cultural elements of the Midwest and the South.

Chart showing regional death rate gaps in urban and rural areas

Start with Louisville, hard by the Ohio River, a city that overachieves when it comes to Americana. Behold Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby. See the many public parks designed by the legendary Frederick Law Olmsted. Downtown is where you will find the Muhammad Ali Center, and the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, and a dizzying number of bars on what promoters have dubbed the Urban Bourbon Trail.

This summer, huge crowds gathered on the south bank of the Ohio for free concerts on Waterfront Wednesdays. Looming over the great lawn is a converted railroad bridge called the Big Four, which at any given moment is full of people walking, cycling or jogging.

But for all its vibrancy, Louisville’s life expectancy is roughly two years shorter than the national average, and the gap has tripled since 1990. Death rates from liver disease and chronic lower lung disease are up. The city has endured a high homicide rate comparable with Chicago’s.

“We have a gun violence epidemic in Louisville that is a public health crisis,” Mayor Craig Greenberg (D) told The Post.

Scott Chasteen, transportation services coordinator for Decatur County Memorial Hospital, transports patient Marilyn Loyd, 70, to her home in rural Greensburg, Ind., in July. Forty years ago, many small towns and rural regions were healthier for adults in the prime of life.

In 1990, the Louisville area, including rural counties in Southern Indiana, was typical of the nation as a whole, The Post found, with adults between 35 and 64 dying at about the same rate as comparable adults nationally. By 2019, adults in their prime were 30 percent more likely to die compared with peers nationally.

Rates of heart disease, lung ailments and liver failure all were worse in the region compared with national trends. The same is true of car accidents, overdoses, homicide and suicide.

And then there’s the rampant disease that’s impossible to miss: obesity.

Endocrinologist Vasdev Lohano examines Shannon McCallister, 50, at the Joslin Diabetes Center in June. McCallister weighed 255 pounds before gastric sleeve surgery three years ago. “I firmly believe it added at least 10 years to my life,” she said.

Lohano, an endocrinologist whose practice sits a short drive north from Louisville, says he has “seen two worlds in my lifetime.”

He means not just Pakistan and the United States, but the past and the present. When he was in medical school in Pakistan, he was taught that a typical adult man weighs 70 kilograms — about 154 pounds. Today, the average man in the United States weighs about 200 pounds. Women on average weigh about 171 pounds — roughly what men weighed in the 1960s.

In 1990, 11.6 percent of adults in America were obese. Now, that figure is 41.9, according to the CDC.

The rate of obesity deaths for adults 35 to 64 doubled from 1979 to 2000, then doubled again from 2000 to 2019. In 2005, a special report in the New England Journal of Medicine warned that the rise of obesity would eventually halt and reverse historical trends in life expectancy. That warning generated little reaction.

Obesity is one reason progress against heart disease, after accelerating between 1980 and 2000, has slowed, experts say. Obesity is poised to overtake tobacco as the No. 1 preventable cause of cancer, according to Otis Brawley, an oncologist and epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University.

Medical science could help turn things around. Diabetes patients are benefiting from new drugs, called GLP-1 agonists — sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy — that provide improved blood-sugar control and can lead to a sharp reduction in weight. But insurance companies, slow to see obesity as a disease, often decline to pay for the drugs for people who do not have diabetes.

David O’Neil, a patient at the Joslin center, lost a leg to diabetes three years ago.

Lohano has been treating David O’Neil, 67, a retired firefighter who lost his left leg to diabetes. When he first visited Lohano’s clinic last year, his blood sugar level was among the highest Lohano had ever seen — “astronomical,” the doctor said.

O’Neil said diabetes runs in his family. Divorced, he lives alone with two cats.

He said he mostly eats frozen dinners purchased at Walmart.

“It’s easier to fix,” he said.

Three years ago, he had the leg amputated.

“I got a walker, but when you got one leg, it’s a hopper,” he said. “I’ve got to get control of this diabetes or I won’t have the other leg.”

Kader’s Market is one of the few food stores in the West End of Louisville. Shopper Fonz Brown noted: “Down here, you have more liquor stores than places where you can actually buy something to eat.”

What happened to this country to enfeeble it so?

There is no singular explanation. It’s not just the stress that is such a constant feature of daily life, weathering bodies at a microscopic level. Or the abundance of high-fructose corn syrup in that 44-ounce cup of soda.

Instead, experts studying the mortality crisis say any plan to restore American vigor will have to look not merely at the specific things that kill people, but at the causes of the causes of illness and death, including social factors. Poor life expectancy, in this view, is the predictable result of the society we have created and tolerated: one riddled with lethal elements, such as inadequate insurance, minimal preventive care, bad diets and a weak economic safety net.

“There is a great deal of harm in the way that we somehow stigmatize social determinants, like that’s code for poor, people of color or something,” said Nunez-Smith, associate dean for health equity research at Yale. And while that risk is not shared evenly, she said, “everyone is at a risk of not having these basic needs met.”

Rachel L. Levine, assistant secretary for health in the Department of Health and Human Services, said in an interview that an administration priority is reducing health disparities highlighted by the pandemic: “It’s foundational to everything we are doing. It is not like we do health equity on Friday afternoon.”

Levine, a pediatrician, pointed to the opioid crisis and lack of universal health coverage as reasons the United States lags peer nations in life expectancy. She emphasized efforts by the Biden administration to improve health trends, including a major campaign to combat cancer and a long-term, multiagency plan to bolster health and resilience.

Public health experts point to major inflection points the past four decades — the 1990s welfare overhaul, the Great Recession, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, changes in the economy and family relationships — that have clouded people’s health.

It is no surprise, Georgetown’s Griffith said, that middle-aged people bear a particular burden. They are “the one group that there’s nobody really paying attention to,” he said. “You have a lot of attention to older adults. You have a lot of attention to adolescents, young adults. There’s not an explicit focus or research area on middle age.”

An accounting of the nation’s health problems can start with the health system. The medical workforce is aging and stretched thin. The country desperately needs thousands more primary care doctors. The incentives for private companies are stacked on the treatment side rather than the prevention side. Policy proposals to change things often run into a buzz saw of special interests.

Anthony Yelder Sr. runs Off the Corner BBQ in Louisville. Yelder, 43, says he has had three heart attacks, starting when he was 36. He blames working too much, a poor diet, smoking and family conflicts.

Michael Imburgia, a Louisville cardiologist, spent most of his career in private medical facilities that expected doctors to see as many patients as possible. He now volunteers at a clinic he founded, Have a Heart, a nonprofit that serves uninsured and underinsured people and where Imburgia can spend more time with patients and understand their circumstances.

Health care is “the only business that doesn’t reward for quality care. All we reward for is volume. Do more, and you’re going to get more money,” Imburgia said.

Elizabeth H. Bradley, president of Vassar College and co-author of “The American Health Care Paradox,” said if the nation’s life-expectancy crisis could be solved by the discovery of drugs, it would be a hot topic. But it’s not, she said, because “you would have to look at everything — the tax code, the education system — it’s too controversial. Most politicians don’t want to open Pandora’s box.”

James “Big Ken” Manuel contends with chronic illnesses at his home in Louisville.

James “Big Ken” Manuel, 67, spent four decades as a union electrician, a proud member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. He has a booming voice, a ready laugh, a big personality.

His life story illustrates a health system built on fragmented and often inadequate insurance, and geared toward treatment rather than prevention. And to the perils of dangerous diets and the consequences of obesity.

He was born and raised in Lake Charles, La., when Black families like his in the Deep South had to navigate the racism of the Jim Crow era. But Manuel talks of his blessings. Two loving parents who worked hard. Friends who stayed close for life. A deeply satisfying career.

These days, retired, he has a modest aspiration: “I want to enjoy my pension.”

For now, it is a challenge to simply get across the room and answer his front door in Louisville’s West End. He needs a walker to get around. Even then, he’s huffing and puffing.

One day in late May, Manuel was at the Have a Heart clinic in downtown. That morning, he weighed 399 pounds.

As he seeks better health, Manuel has a modest wish: “I want to be able to enjoy my pension.”

Manuel drove to the clinic one morning with a bag containing all his medicines. Hydralazine. Torsemide. Atorvastatin. Metformin. Carbetol. Benzonatate. Prednisone. Fistfuls of medicine for a swarm of cardiometabolic diseases.

“It’s a lot of medicine. And it’s expensive. Eating up my pension,” Manuel said.

He was desperate to get stronger, because he was engaged to be married in a few months.

“I got to be able to walk down the aisle,” he said.

Mary Masden, 60, dated Manuel for years before deciding to get married.

She remembers when Manuel had more mobility. He could still dance. She is praying he will be able to dance again someday.

“I want him here for another 20, 30 years,” she said. “I don’t want to worry about him not waking up because he can’t breathe.”

On Sept. 2, Manuel and Masden were joined in marriage, and he did walk her down the aisle. He thought better of trying to jump, ceremonially, over the broom. He and his bride honeymooned at a resort in French Lick, Ind. The wedding, they agreed, was beautiful.